Wednesday, 26th March 2025.

By inAfrika Reporter

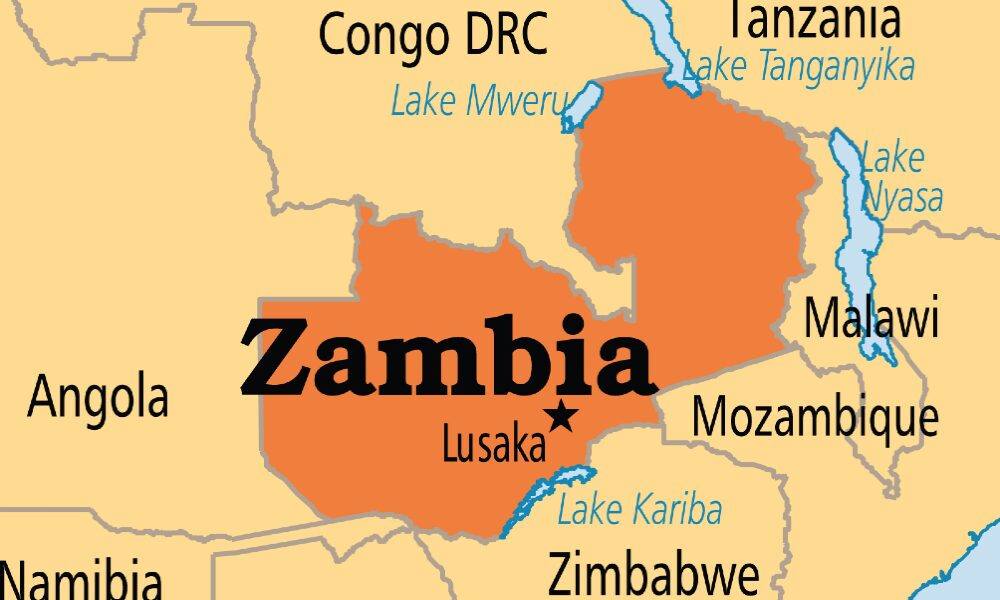

Kenya’s State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are facing a tightening credit squeeze, as commercial banks dramatically cut back on lending amid a new fiscal regime that prioritizes accountability over bailouts. In the year ending December 2024, local banks trimmed loans to parastatals by nearly Sh31 billion—a 32 percent drop that marked the steepest decline in over ten years.

The sharp reduction signals a deliberate shift in how both the financial sector and the government are approaching the chronic debt crisis in State-run agencies. Total outstanding credit to parastatals dropped to Sh65.4 billion—rolling back to figures last seen in 2015.

While public entities have historically relied on government goodwill and unrestricted access to credit, this era appears to be drawing to a close.

The lending drought was triggered by a directive from the National Treasury that effectively blocks financially undisciplined parastatals from acquiring fresh loans or receiving government guarantees. This policy, enforced under Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi, follows years of rising defaults and ballooning contingent liabilities that have left the taxpayer increasingly exposed.

The Treasury’s position is simple: entities that have failed to meet loan obligations or pay suppliers will no longer be supported through official channels. More than half of the parastatals with outstanding loans—31 out of 54—made no repayments during the last financial year, underlining the extent of fiscal indiscipline within the system.

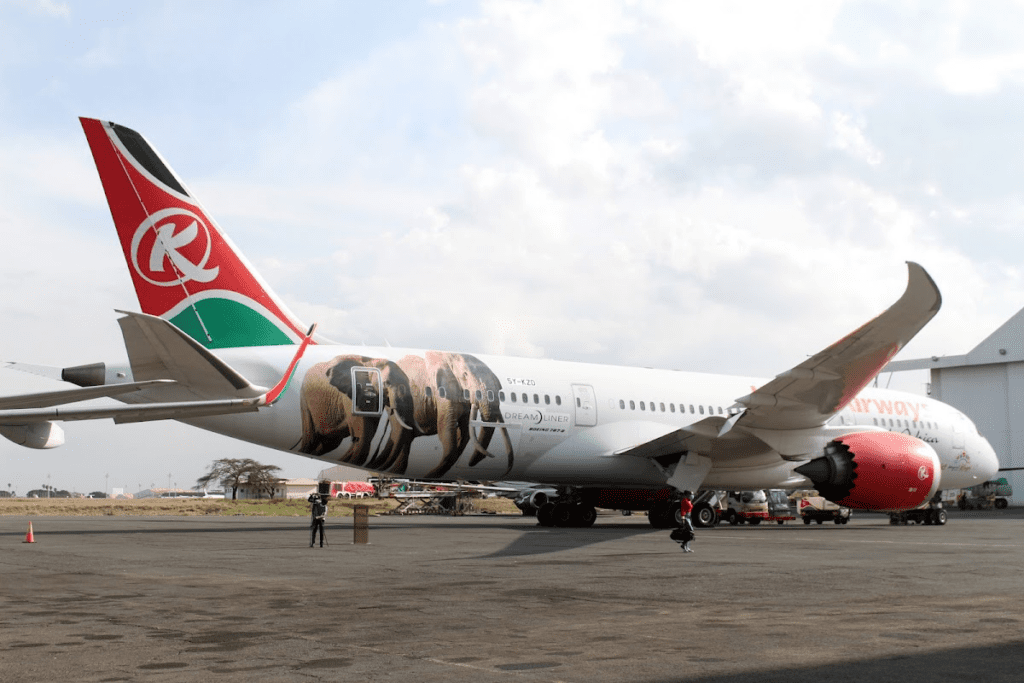

One of the more notable examples was Kenya Airways, which had to be rescued by the government with a Sh17.4 billion intervention after failing to honor a loan due in the last financial year. The flag carrier’s bailout adds to an already growing burden on public coffers.

Kenya’s parastatals have accrued a cumulative debt stock of approximately Sh1.38 trillion, the majority of which comes from external development financiers and government on-lending. But the nature of the debt raises deeper questions. Much of the borrowed funds have reportedly been channelled into paying wages and sustaining operations rather than driving capital investment.

This trend, flagged by the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), reflects a fundamental misalignment between borrowing and productivity. Long-term debt has been used for short-term consumption, eroding the ability of these institutions to generate returns and undermining their future viability.

The CBK has previously cautioned banks about the risks of funding State corporations, particularly when such funding supports recurrent expenditure over development. That caution is now manifesting in action, with the banking sector scaling back exposure in favor of financial safety and higher-quality lending.

Alongside the cut in bank credit, the government is doubling down on fiscal controls within parastatals. In newly issued budgetary guidelines, CEOs and accounting officers of SOEs have been warned that unauthorized expenditures—especially those made without Treasury or line ministry approvals—will result in personal liability.

This administrative tightening is backed by the Public Finance Management Act, which gives the Treasury wide powers to restrict borrowing, demand concurrence on financial decisions, and hold public officers accountable for irregularities. The shift aims to instil discipline in an environment where past laxity has led to reckless borrowing and ineffective spending.

Meanwhile, arrears to suppliers and contractors had reached Sh426.3 billion by the end of December 2024, indicating that the debt crisis extends well beyond formal lending. These unpaid bills continue to paralyze sections of the economy, especially SMEs that rely on government contracts for cash flow.

The backdrop to all this is a broader recalibration in Kenya’s credit market. In 2024, banks significantly raised borrowing costs—some up to 24 percent—as they responded to higher benchmark interest rates. While this helped bring inflation under control—averaging 4.47 percent compared to 7.7 percent the previous year—it also discouraged new borrowing across the board.

Private sector credit issuance shrank by 1.37 percent in 2024, reaching Sh3.86 trillion by year-end. This rare contraction was last seen in 2002, and partly stems from banks’ cautious stance on risk, which saw them sideline both distressed firms and financially unstable public bodies.

A strengthening shilling against the dollar further contributed to the decline, reducing the value of dollar-denominated debt on conversion and easing some of the credit pressure in local currency terms.

For decades, Kenya’s parastatals have played strategic roles in the economy—but many have also become synonymous with inefficiency, mismanagement, and endless rescue packages. The latest developments suggest the Treasury is intent on ending this cycle.

The withdrawal of government guarantees for underperforming entities is a message that the age of automatic bailouts is coming to an end. Going forward, only institutions that can demonstrate fiscal prudence and repayment capacity are likely to attract credit—public or private.

This shift may force a long-overdue transformation in how State corporations operate. The hope is that by enforcing strict lending criteria and reducing dependency on emergency interventions, SOEs will be pushed toward internal reforms, improved governance, and financial sustainability.

For lenders, this means a more rational risk landscape. For taxpayers, it could mean fewer liabilities passed down the line. And for parastatals, it represents a challenge—and an opportunity—to clean house before the credit window closes entirely.